Since Atlanta and Yoqne’am Illit and Megiddo are partnership cities, Yonatan and Stella have created local guides for their hometowns. We hope you enjoy getting to know the cities better from the perspective of high school Jewish teenagers! By Yonatan Cohen & Stella Mackler, May Amplifying Israel Teen Fellows

Everything to do and see in Atlanta!

Atlanta is an incredible city. It has a rich and complicated history which is evident throughout the city. In this guide, you will find great sight-seeing spots, delicious restaurants, historic neighborhoods and so much more!

Dining

Where to find that necessary cup of coffee: One of my favorite cafes in Atlanta is Apotheos Roastery, formerly known as San Francisco Coffee. They have two locations, and one of them happens to be super close to where I live! They roast, brew, and bag their own beans and offer classic drinks like lattes and cappuccinos alongside a rotating seasonal menu. They also serve pastries fresh out of the oven and offer breakfast toast, sandwiches, and other local products like King of Pops.

Lunchtime bite: Take a quick but filling stop for lunch at Mediterranean Grill (aka Med Grill). They are 100% Halal (except for the gyros) and serve many familiar favorites like hummus, pita wraps, lentil soup, and so much more. The greek potatoes are a particular standout. Its a common site to see people walking around with takeout containers filled with just that. Med Grill is perfectly located across the street from Piedmont Park and the Beltline, making it a convenient spot for your day of exploring.

Dinner: For the last meal of the day, make your way to Doc Cheys, somewhat of a hidden gem in the neighborhood of Morningside. They serve a wide array of pan-Asian fare with ever-changing weekly specials. I have grown up spending Saturday nights with the grandparents and friends here, and it’s not just because of the food. The sense of community the restaurant welcomes you with is impossible to miss. The waiters there are the same ones that have been there since I was seven years old and the takeout guy and I are on a first name basis. Some notable dishes include the thai peanut salad and the mongolian stir fry. Doc Cheys is vegetarian/vegan friendly and most dishes can be served with tofu.

Sightseeing/touristy spots

The Beltline: The Beltline is “a sustainable redevelopment” project that will ultimately connect 45 intown neighborhoods via a 22-mile loop of multi-use trails, modern streetcar, and parks – all based on railroad corridors that formerly encircled Atlanta. The Eastside trail is my recommended starting place. It is covered with murals and other forms of public art. There is a skate park, playground, and it often hosts festivals, like the lantern parade.

Ponce City Market: Ponce City Market is a multi-use building with shopping, fitness, and a dining hall all in one. It is located inside a former Sears factory and is conveniently right off the Beltline. There are some great shops, like Citizen Supply and Modern Mystic, and places to grab a bite, like St.Germain Bakery. There is also an amusement park and restaurant on the roof, with very pretty views at night.

Piedmont Park: Of all the places to see on this list, Piedmont Park is the one you absolutely cannot skip. The greenspace is the perfect place for a walk by the lake, a picnic, an exercise day, or just plain old people watching. It stretches from tenth street into the heart of midtown and is the site of the Music Midtown festival in the fall. There is a farmers market there every Saturday morning, and festivals are a common occurrence in the summer.

Historic Neighborhoods

Virginia Highlands (VaHi): Named after the intersection of Virginal Avenue and North Highland Avenue, the VaHi neighborhood is famous for its historic houses built between the 1910s-1930s.

Old Fourth Ward (O4W): O4W is located just east of downtown and is the birthplace of Martin Luther King Jr.America’s best known civil rights leaders. It is also home to a giant park, Historic Fourth Ward Park, which includes a skate park, splash pad, and outdoor theater. Many of the best restaurants in Atlanta are located within O4W.

Sweet Auburn: This area is a historic African American neighborhood and was designated as a National Historic Landmark District in 1976. The first Black newspaper in the US, the Atlanta Daily World, began in Sweet Auburn. The neighborhood is also home to 4 prominent Black churches, the Civil Right Walk of Fame, and the Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History.

What Can You Do in Yoqne’am Illit?

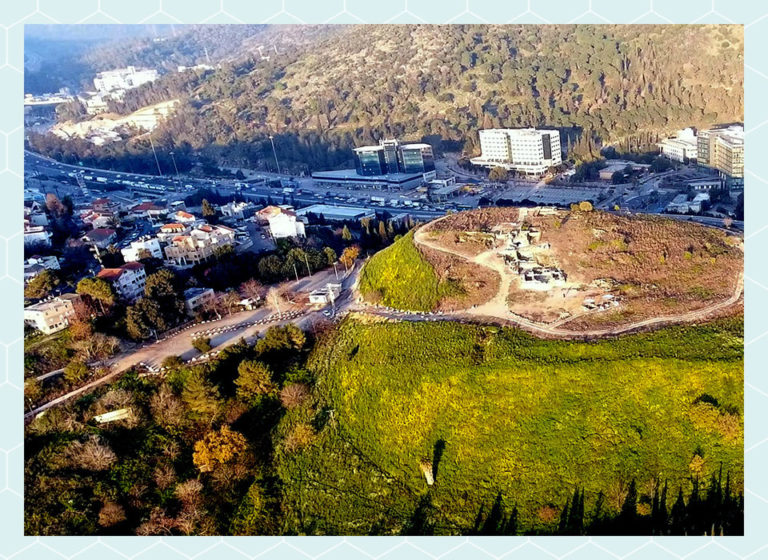

Yoqneam is a small city in northern Israel. It’s about 20 kilometers from the city of Haifa and about 80 kilometers from Tel-Aviv. The city is located alongside Israel’s main highways – highway 70 and highway 6, enabling you to reach the center of Israel and its northern areas quickly. Yoqneam is known as “Israel’s Startup Village,” because its’ hi-tech hub is surrounded by forest and small communities. Yoqneam was founded in 1950 and became a city in 2007. Yoqneam is an attractive city to many young families who seek to live in a small and quiet, village-like place, yet enjoy all the things a city can offer, as described below.

Shopping in Yoqneam

Yoqneam has several shopping centers that include a mall and an open shopping domain where you can find famous clothing shops, supermarkets, homeware, hardware shops and more. All of them offer free parking, which shoppers find very convenient.

Dining in Yoqneam

Yoqneam has a few well-known restaurants, coffee shops and food and beverage counters you can enjoy. One of the most popular restaurants in the city is “BBB,” which is an exclusive burger diner where people from all over Israel come to eat.

Sport in Yoqneam ⚽

If you’re looking to keep in shape while in Yoqneam, you have come to the right place. Yoqneam offers a big country club where you can go to the gym, train at different sport classes, such as: Pilates, Yoga, Zumba and more, and swim in an outdoor or an indoor pool. Aside of the country club, you can find a big gym at the mall and a smaller one at the industrial area.

Culture in Yoqneam

If you’re fond of shows and plays, you can come to Yoqneam theatre. This theatre hosts popular shows and actors from all over Israel. There is a miniatures museum and a winery.

Since Yoqneam is mentioned in the Bible, there is archeological evidence that the area exists for 3,500 years. In the new archeological visitors center, you can find items aged thousands of years which tell the story of the city with its rich past.

Nature in Yoqneam

Yoqneam was built on a hill in the middle of nature, therefore, nature surrounds all its areas. There are wide parks where you can take a walk or just sit by the pond and relax. There is a stream that runs through the city where you can walk beside it. There is a big forest and a spacious field area where you can hike and ride a bike.